Pacman Championship Edition 2 (Review)

Source: Cashmoneys

Price: £9.99

Where To Get It: Steam

Pacman, it seems, has been refined down to a science. Somewhere, out there, a mathematician is looking at this latest offering from Namco Bandai, and doing complex equations to work out what the absolute maximum possible score is. And most likely, there’s also a competitive player who would beat that score.

If I could give one recommendation to Pacman: Championship Edition 2, it’s that it made me appreciate exactly how much calculation can go into a game. Let’s talk about why.

So, let’s start with the simplest layout. Nearly always, it’s something like this. A simple pattern. Following it through to the end, without backtracking, is nice and simple. It takes ten seconds. Each pellet gives you a small amount of points. Collect them all, get a fruit, which is more points, and the next pattern appears. Do that three times, and the fourth is a power pellet. Which lets you eat the ghosts, which bags you loads of points. Another four, and it’s a power pellet every round. So far, so simple.

Now add in a complication: You don’t have to get all the pellets to get the fruit, and thus the next pattern. You can move quicker, get to that endless power pellet stage a little earlier. But you still need more pellets each round, and, toward the end, you need more than you need for a power pellet to get a fruit.

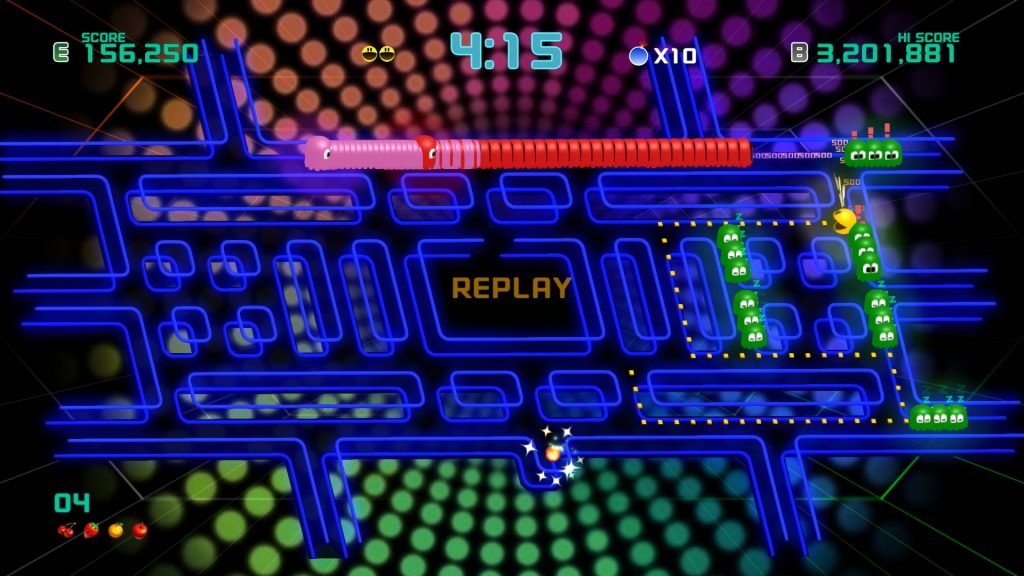

Now add in another one: There are sleeping mini-ghosts. The more you pass close by, the more get added to the train of our old friends, Inky, Blinky, Pinky, and Clyde. They add even more points when you get to the power pellet stage, and long trains appear to give the most points… So pathing to achieve the maximum amount of mini-ghostage is a consideration. But of course, you still have a minimum pellet quota to consider, and you don’t want to be wasting time backtracking without picking up pellets.

Now add in a final base complication: If you know Pac-Man, you’d know that the ghosts run away from you, or try to, when you pick up a power pellet. They, quite sensibly, don’t want to get wakka’d , although it never permanently kills them. But they can only run along certain paths, which are, thankfully, made clear when you get a power pellet. So you have to path to catch the ghosts as quickly as possible.

Nine stages, three and a half versions (Single Train, Regular, and Extreme… Practice I guess too. ;P ), and the layout of each doesn’t change. Five minutes, with one time extension at a high score. And some have their own complications, such as jump-pads. But it starts with a simple path to follow, and slowly makes it more complex, makes the game a little bit quicker, until it’s just as much an exercise in reflex as in logic. The aim, of course, being to achieve the highest score in the time allotted.

Pacman, folks, is Newtonian Physics: The Game. And that Championship Edition 2 demonstrates this, this exercise in getting the most efficiency out of a system with predictable rules (The ghosts have set patterns, the pellets have set patterns, even the things that run away from you, such as later power pellets and fruit, follow set patterns… Including stopping when they’re not “threatened” to trick you) in play? Is to its credit.

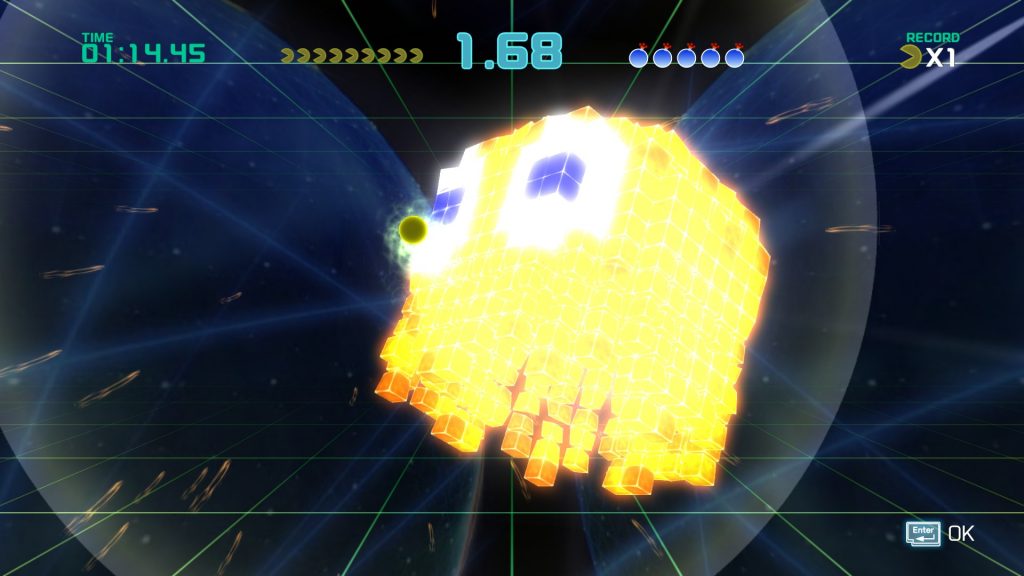

Of course, I haven’t talked about the other aspects, because, let us not forget, Pacman is also a game with history. Visually, it makes reference to a lot of versions of the game, from the isometric view, lego bricks, and 3d ghosts of Pac-Mania (1987), to the emphasised pixels of cleaner versions, to the simple vector walls and flat ghosts of the originals, several camera angles (Including both isometric projections… Which I’ve always secretly hated), and the feature to either play with any of these visual styles, or, even better to my mind, play with a simple style, then watch an action replay in any of the others. Musically, it’s pumping beats, some remixes of older pacman tunes, but all delightful tunes, and fitting to the game.

Then… There’s Adventure Mode. Unlocked, as most features are in this game, by doing well in Score Attack, adventure mode is basically themed challenges. Generally, that would be “Get X fruit.” Collect it quickly, the timer resets. Take too long, and you just lose. Beat enough of them, and you unlock a boss level. And those aren’t too different from normal play. Soooo… Adventure Mode is sort of the weakest part of the game.

What’s strong, however, is the tutorials section. Pacman is a relatively simple game. However, it does have some nuances, and this game? Kindly walks you through pretty much all of them. Which is a pleasure.

So… Apart from Adventure Mode, the game is tightly designed, visually appealing, and a good example of how yes, you can refine a concept that’s been played. Namco Bandai have been proving that with Pacman for some time, and, with Championship Edition 2, have shown that you can make a game with scientific precision.

The Mad Welshman opened his mouth and popped in a tic-tac. Then another. Then another. Measured. One day, he too would eat a ghost. One day.

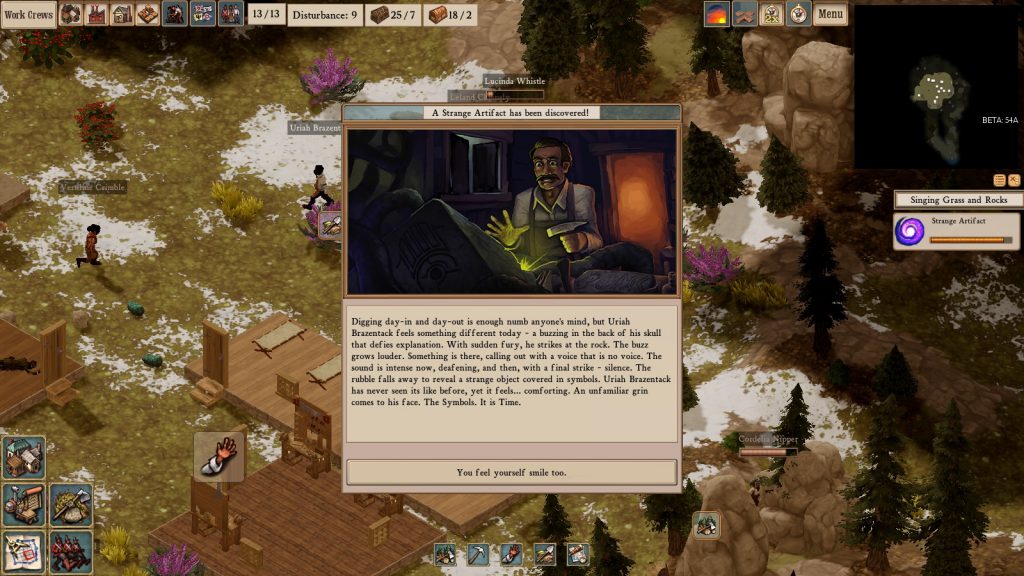

!["We need Graveyard Space [But we decided to stop flattening terrain because we're workshoppers now...]"](https://themadwelshman.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/20160911192645_1-1024x576.jpg)