RPG Worlds Can Do More

Some say that games are a limited creation, only able to replicate certain experiences. Indeed, this was a core argument behind the “Games cannot be art” statement: They were believed (Although contradictory evidence has existed since the early days) unable to speak to experience, or make statements, or do many of the things art can do. Indeed, as time has gone by, we’ve had to invent new genres to talk about new games, and not a year goes by without me looking at something and saying “Ah, that’s pretty innovative!”… And meaning it. Unlike many times I’ve heard the word (That’s no doubt an article for another day…)

But games do have a limiting factor, and it’s a limiting factor that doesn’t promise to go away: The creativity of its makers. I’m going to pick on DnD games in this case, because there are interesting facets of Dungeons and Dragons universes past and present that RPGs, as my chosen example, just don’t replicate. And it’s not that it’s impossible… Tell a particularly stubborn or creative game designer something is impossible, or even “hard to make entertaining”, and there is a strong possibility that you will find, some time later, that they’ve proven you wrong. Pacifist games. World Simulations. Multiple path murder mysteries… I could find you examples of these, and quite a few more out there ones. There’s a game about the dangers of assuming simulations can give clues to historical events (Opera Omnia, by Increpare). There’s at least two games about jobs of crushing futility (Papers Please and Cart Life). There are procedurally generated murder mysteries (A small, but fun example is The Inquisitor, from ProcJam 2014). But let’s get back to DnD. Specifically, Dark Sun, Ravenloft, and (briefly) Forgotten Realms.

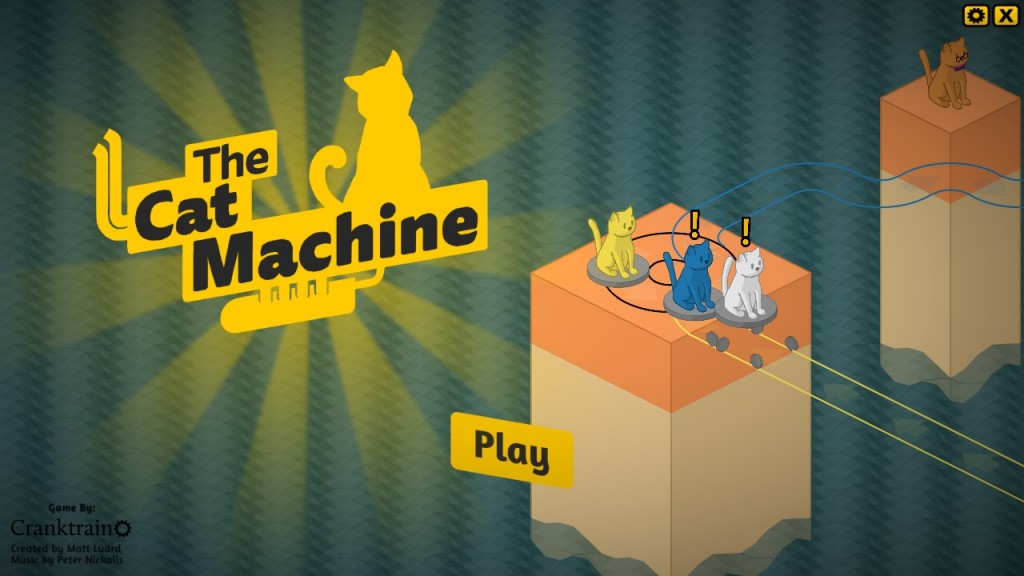

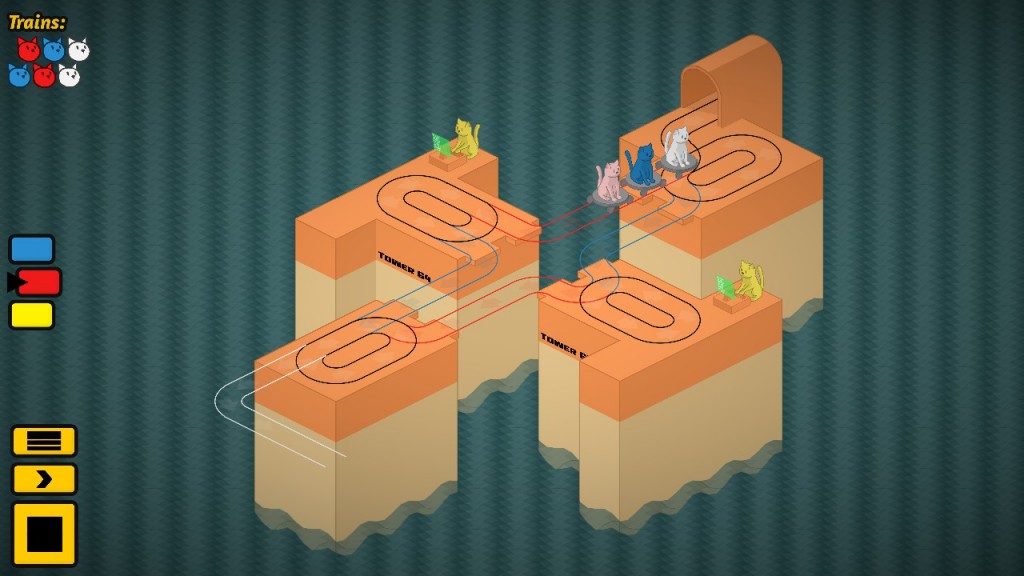

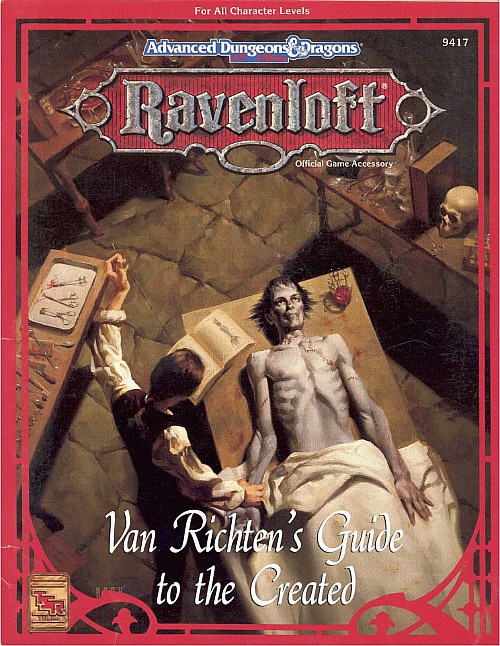

There are two Dark Sun games, two Ravenloft games, and several Forgotten Realms games, but each setting has elements that games struggle to replicate. Let’s start with the most interesting one, Ravenloft. Ravenloft was TSR’s attempt at horror, and one of its core supplement series are Van Richten’s Guides. Van Richten’s Guides, much like Trollpak, many 90s RPGs, and countless race supplements have done (or at least attempted), attempted to make monsters we normally fought as fodder interesting, unique, and, because horror monsters have to be more powerful than the protagonists in some fashion, harder to dismiss as Just Another Kill. It explores it from the perspective of a premiere monster hunter, all the ways they could be wrong, all the ways they have been wrong, and what it cost. They’re pretty good reads, and, for good or for ill, are also good examples of how tabletop RPGs deal with making threats interesting.

And then you play the two games and… It’s set pieces, a series of fights and puzzles. They’re limited, not only by the technology of the time (The Ravenloft games, and the one FR game using the same engine, Menzoberranzan, were notoriously picky to run for the time, and are still technically tile based, first person view games), but by game design thinking of the time. RPGs must have a BOSS MONSTER… So for the first game, they picked the most iconic, Strahd Von Zarovich, Darklord of Barovia… A character who can never actually be defeated, due to the way Ravenloft works. And the means of defeating him is, of course, a McGuffin. Along the way, you can cure a werewolf of his affliction. Sounds like an average day for the adventurer, right? Oh, and they make it horrific by having endlessly respawning monsters.

What results is a tiresome slog. But, within their limitations, they try to be atmospheric, in the sound design, the speeches by (rare) scared peasants, gypsies, and, of course, Strahd’s Vampiric Monologue… But what it amounts to is a Dungeon Bash By Any Other Name, complete with Helpful, But Oddly Powerless Deity that gives you the knowledge that you need the McGuffin of Vague Holiness, the Potion of Protection From Arbitrary Obstacle (Obtained by making sure you collect every coin in a certain dungeon, and giving them to the local Vistani Wise Woman), and, of course, the RPG equivalent of an 80s Training Montage (Grinding on monsters until you have the right level to safely proceed in the story. Not helped by the fact that some monsters drain experience levels. Have fuuuun!)

Now let’s compare that to the experience in tabletop. Strahd as a direct enemy is usually right out. He has Cursed Plot Armour (No really, he’s cursed to forever make the same mistakes, to never outright be killed, all for the giggles of cosmic entities who hate everything nice and fluffy). On top of that, he’s somewhat boring, precisely because of this. It’s a common problem with making Ravenloft a campaign setting: As soon as you actually involve the Big Bads, or the players try to get out of Dodge, it’s a rapid downward spiral. And, due to the way DnD works, eventually you will.

While each concentrates on a single type of monster, each of Van Richten’s Guides had interesting ideas.

But the setting takes a great effort to keep things interesting. Yes, McGuffins are still involved, to some extent or another, but they most often take the form of symbolic weaknesses. Certain things nearly always work, such as a stake to the heart and decapitation in the case of vampires, but other things depend on the vampire. In fact, a big part of a monster hunt in Ravenloft is recognising the monster for what it is. People are disappearing in the area? Not good enough. That could be quite a few things. There’s investigation, both in the sense of becoming aware of the type of threat, and investigating how to defeat it, with real consequences for fucking up. And, competently told, this story is suspenseful, can be heartbreaking and entertaining, and has the potential for an interesting game. There’s lots of variation possible there, too. For example, curing a werewolf of his affliction could, due to the way it works, take a small campaign and still fail, whether due to the person not wanting to be cured, or not having correctly gone through all the steps, and, even when things are done right, it involves an immense effort of will on the part of the afflicted. Keep in mind, even failure can be made interesting if you do it right.

Meanwhile, back in the computer game world, Strahd patiently sits in his castle and waits equally patiently for you to jack him up. He’s mentioned as the owner of all he surveys (Which, as an aside, gets around the vampire weakness of not being able to enter a home. He owns all the homes in Barovia), but… He’s a glorified boss monster.

These beetles actually have brains. And mind control. But here, they’re a monster with some ranged attacks.

Dark Sun, also, is an interesting setting. Magic is harmful to the world’s well being, relying on life force to flourish. Water and metal are scarce, and survival is considered more important than trust. Even in the desert, there’s a flourishing (and lethal) ecosystem, and unwise magic or decisions can make an area barren forever. There are entire cultures, with their society dictated by the world they live in, but when you get to the computer games… Again, due to a limitation of beliefs and mechanics of the time, it’s… Once again, mostly a series of fights and puzzles. The closest you come to any of this interesting stuff is that defilers aren’t allowed as characters, only enemies (But become less effective as enemies in the second game’s fights as less and less foliage becomes available as fuel), a few sidequests where you can be betrayed, or help a village or person survive (Occasionally involving water, which you’ll otherwise never use), and the fact that the endgame is easier (Although still a massive, painful battle) if you’re not a dick. Oh, and sometimes weapons break, if they’re not steel.

You could have a Thri’Kreen (Mantis person) in your party, and never be aware of their customs, their culture, their language, or their psychology (It’s interesting stuff, and the book you want to read there is “Thri-Kreen of Athas”, from 2E AD&D… TSR #2437). By the end of the game, you’ve got metal plate armour for everyone who can use it, steel weapons for everyone who can use them, and you’re quite happily roaming through scorching deserts with all this on, giving nary a single fuck about the consequences. Equally, the plant life, the ecology… They’re just monsters to beat up.

Seriously, for all that both settings got silly, the computer games really don’t give you much of a clue as to how much effort went into each setting. Even Forgotten Realms, a world where the gods literally depend on belief for their survival, and can act directly in the world, in a setting with enough computer games to fill a small bookshelf (If you so chose), don’t really give you as much support between the setting and mechanics as you may like. Yes, not even Baldur’s Gate 2, widely considered to be the best Forgotten Realms computer game around. There’s an excellent and informative VideoBrains talk on the subject of religion in games by Jenni Goodchild here, and even though Dragon Age is the main example, it applies equally well to Forgotten Realms.

Now, you may be saying that size, or complexity, is an issue here. And in a sense, you’d be right. Previously, this was the case. But it’s much less of a problem now, and size, or complexity, aren’t the main issues here. The main issue is one of how well games sync up with the things they’re trying to talk about or portray. We talk about The Last of Us because of how it deals with survival, and relationships, and responsibility. We talk about Bioshock because of how it deals with choice, and the degradation of ideals. We talk about Analogue: A Hate Story because of, again, relationships… But also how the known past can be misleading, and about societal expectations, toxic or otherwise. These games, while they are by no means perfect, are held up as games that do the job they aimed for particularly well. We don’t have as many problems with authorial intent in these examples as otherwise, because it’s more often the case that the game laser focuses on these specific issues.

Sometimes, you just want to make or play a dungeon bash, and that’s cool. Done well, it’s entertaining, and it’s all good. But that is by no means the only kind of game you can make, and I think it’s time that more people realised that. I wouldn’t mind seeing an Eberron game about being an Inquisitive. Or a Dark Sun game about a tribe’s survival, or the ecosystem of the world. I wouldn’t mind, in short, seeing more games that explore their settings. And I pick on RPGs, because, very often, we’re too focused on The Hero’s Journey, or on pretty numbers going up and Big Bads. There are games out there that do more… And there can be more. While this article picked somewhat on licensed RPGs (For the simple reason that licensed media often vary widely in quality), it’s true of pretty much any setting or genre… How you show an aspect of your setting is important. And you can completely miss aspects that people might find more interesting than you’ve actually shown.